Fort Donelson: Grant’s Breakthrough Victory and the Rise of the Western Sharpshooters

- Owen Doak

- Jul 23, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Jul 24, 2025

In the summer of 2024, I had the privilege of visiting the National Park Service's Fort Donelson National Battlefield Historic Site. After working on my novel for over a year, I was looking forward to seeing the location of the battle that made my grandfather's regiment, "Birge's Western Sharpshooters," famous. Granted, no one today except Civil War buffs and a few teachers and professors have heard of the "Western Sharpshooters." But after the Battle of Fort Donelson, the Western Sharpshooters were featured in the New York Times in 1862. That February, the Western Sharpshooters had their fifteen minutes of fame. Sadly, in 2025, I think nine out of ten Americans have no idea what happened at Fort Donelson or why it is important.

By early February 1862, Corporal John W. N. Doak and Company E were eager to finally "see the elephant." They had skirmished with rebels in Missouri but had not yet experienced a major battle. They were soon to join General Ulysses S. Grant's Army in Tennessee.

Union high command in the Western Theater focused on controlling railroads and rivers. Union soldiers and Confederate rebels fought the Battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson over control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, respectively. On February 6, 1862, Union Flag Officer Andrew Foote's flotilla swiftly defeated Fort Henry's Confederate defenders. Grant's army arrived after the surrender. The Union took only 79 prisoners, while over 2,000 rebels escaped twelve miles due east to Fort Donelson.

The Western Sharpshooters reached Paducah, Kentucky, on February 7th, missing the Battle of Fort Henry entirely. They traveled up the Tennessee River and came ashore near Fort Henry. Grant wanted to attack Fort Donelson immediately, but he was not able to. His entire army was delayed by heavy rains and flash flooding. Five days later, Grant's army, including the Western Sharpshooters at the rear of his column, marched 12 miles east to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. The rain stopped, and temperatures rose into the 70s, prompting many Union soldiers to discard their coats and blankets—a decision they would soon regret.

The Western Sharpshooters arrived on the evening of February 12th and likely camped near C.F. Smith's name on the above map. As suggested by the map above, the topography of Fort Donelson and Dover, Tennessee, is a series of ridges and ridgelines along with several creeks that flow into the Cumberland River. Under General C. F. Smith, commander of the 2nd Division, the Western Sharpshooters stayed on the extreme left of the Union position during the three-day battle as part of Colonel Jacob G. Lauman's 4th Brigade. On the first night, they bivouacked perhaps less than a mile from the rebels camped in the trenches along the outer defenses of Fort Donelson.

On February 13th, Grant consulted with Flag Officer Andrew Foote on the Cumberland River, hoping the navy could force Fort Donelson's surrender just as it did at Fort Henry. He instructed Generals C.F. Smith and John McClernand not to engage the enemy, but both ignored him and tested the rebel defenses in front of them.

The Western Sharpshooters charged into battle down a ravine toward the rebels, deploying as skirmishers. As they came under enemy fire, many sought cover behind fallen timber or in trees. They began taking shots at the rebels on the ridgeline in front of them, some 400 to 600 yards away. The Western Sharpshooters, armed with the deadly accurate Dimick Rifles, could hit a man from 500 yards; some could hit a man from 800 yards. The rebels had the high ground and were protected by their earthworks, but they were outgunned. Their muskets were accurate at seventy yards or less.

On that first day of the battle, Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest arrived with his cavalry to check on the Confederate right. According to historian Benjamin Cooling, Forrest grew "annoyed by one pesky marksman from the famed Birge's Western Sharpshooters, borrowed a Maynard rifle, and shot the offender out of a tree" (Cooling, The Campaign for Fort Donelson, "National Park Civil War Series," page 25). The "pesky marksman" was likely the first Western Sharpshooter to die in the Battle of Fort Donelson.

The rebels soon positioned twelve cannons on their ridgeline to defend their position. The Western Sharpshooters retreated to their own rifle pits and effectively targeted the rebel gunners, silencing their batteries for three days. As reported by The New York Times: “Berges’ Sharpshooters have done good service. They kept several of the enemy’s guns idle by picking off the cannoneers as fast as they appeared at the guns.”

February 14th dawned frigid, with temperatures overnight dropping to twelve degrees. The balmy weather of February 12th was forgotten as rain turned to sleet and then to snow. Still, the Western Sharpshooters continued their grisly work; the Confederate artillery remained silent.

At 2:00 p.m., on the Cumberland River, the Union's brown water navy began their assault on Fort Donelson. But the rebels were well prepared, and their river batteries were well positioned. (See photos above.) This would not be a repeat of Fort Henry. Foote's Union flotilla was decimated by the fort's guns. Flag Officer Andrew Foote's flotilla was soundly defeated, with 54 dead sailors and most of his fleet severely disabled. Victory would not be won by the navy at Fort Donelson.

On the night of February 14th-15th, the miserable weather conditions continued. The agony of the ice-cold weather tormented both patriots and traitors alike. Arminius Bill, a seventeen-year-old Western Sharpshooter from Sheffield, Illinois, described the conditions in his diary: "[n]o tents, nor blankets, nor fires, nor any food for us yet . . . Half-starved, we sat, squatted, and stood. Some slept as they sat or squatted in the mud, with faces black from smoke . . . Our clothing was soaked and muddy . . . Some of the men constructed long huts out of branches and leaves and, crawling in close together, would try to gather warmth enough to sleep." (Bill, Arminius. The Civil War Diary of Arminius Bill, Bill Memorial Library, Connecticut Digital Archive)

Although the rebels defeated the Union navy on the 14th, their position had actually deteriorated. Another division, the 3rd Division led by General Lew Wallace, arrived to complete the investment of the fort. The 15,000 rebel defenders were now surrounded by Grant's Army of 25,000. Possessing very few boats, a river escape was impossible. On the Union right, the rebels attempted a breakout attack, including an artillery barrage and infantry attacks. The fighting on the Union right was particularly brutal and included hand-to-hand combat and bayonet charges. The Union forces retreated, leaving an escape route for the rebels. But then the rebels went back to their camps and trenches in the fort and the town of Dover. Why? No one really knows. Inept leadership? Miscommunication? There was certainly some confusion between Generals Pillow, Floyd, and Buckner. Although the escape route was open for a couple of hours, the rebels did not press their advantage.

Alerted to the crisis, Grant swung into action. He mounted his horse and galloped across the battlefield from the Cumberland River to the Union center, where he ordered a counterattack on the Union right. He then conferred with General C.F. Smith on the Union left, directing him to lead an attack on the vulnerable Confederate right.

General Smith did not hesitate. He ordered his 4th Brigade to assemble. Sitting erect on his horse and resplendent in his general’s uniform, he addressed them from his mount, projecting his baritone voice loudly across the wintry landscape: “Come on, you volunteers, come on. This is your chance. You volunteered to be killed for love of country... I'm only a soldier, and don't want to be killed, but you came to be killed and now you can be.” (Cunningham, O. Edward, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862. Page 64. )

The Western Sharpshooters played a significant role in General Smith's attack, following the 2nd Iowa in the assault on the rebel trenches. Historian Benjamin Cooling notes that a mounted General Smith, at great risk to himself, personally led his division up the steep slope to Buckner's trenches near the Eddyville Road. The troops advanced steadily, motivated by Smith's cries: "Damn you, gentlemen, I see skulkers!" A young participant recalled being terrified but was inspired by Smith's leadership: "I saw the Old Man's white mustache over his shoulder and went on."

Amidst the murderous fire of muskets and rifles, the 2nd Iowa paid a heavy price. Three of the 2nd Iowa’s color bearers were shot and killed in quick succession. After the rebels killed a third color bearer, the 2nd Iowa’s Corporal Voltaire P. Twombly took up the regimental flag without hesitation. He was soon hit in the chest by a spent cannonball. Knocked to the ground but uninjured, Twombly jumped back up to his feet. Twombly led the 2nd Iowa up the last twenty yards of the ravine and into the rebel trenches.

Twombly climbed to the top of the rebel trench and waved the regimental flag back and forth triumphantly. Fighting, including hand-to-hand combat, raged all around him. Unable to hold back the rush of Union attackers, dozens of rebels of the 30th Tennessee panicked and retreated. In 1895, Corporal Voltaire P. Twombly of the 2nd Iowa received the Medal of Honor for his gallantry in battle at Fort Donelson.

Smith's attack succeeded as Colonel Lauman's brigade overwhelmed the 30th Tennessee, forcing them to retreat a quarter mile closer to the fort and form a final defensive line under General Simon Buckner.

On the night of February 15th-16th, the rebels faced a dire situation. Their army was surrounded, and the men were cold, hungry, and near mutiny. At the Dover Hotel, Generals John B. Floyd, Gideon Pillow, and Simon Buckner decided to surrender the fort. Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, also present at the meeting, refused to surrender and escaped to Nashville with his cavalry. Floyd and Pillow fled via the Cumberland River with a couple of regiments, leaving General Buckner to handle the surrender. They hoped Grant, a former friend of Buckner from their West Point days, would treat him fairly. Floyd and Pillow feared the consequences of surrendering.

To be sure, General John B. Floyd had reason to fear capture, as he was one of the worst American traitors since Benedict Arnold. As Secretary of War under President Buchanan, he transferred 115,000 muskets to southern states and attempted to send hundreds of cannons to the deep south in December 1860, benefiting the southern states just before the Confederacy was established. Unionists and patriotic Americans viewed Floyd as guilty of treason even before the Civil War began.

Grant's response to Buckner's request for terms was legendary: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” (Chernow, Grant, p. 182) Buckner was shocked by Grant's response, but he had no choice but to accept his "ungenerous and unchivalrous terms."

In the aftermath of victory, Northern newspapers immediately hailed Grant as a hero, dubbing him "Unconditional Surrender" Grant. Lincoln was pleased to finally have a victory and a "general who fights." The Western Sharpshooters were honored to be the second regiment to enter Fort Donelson, following the 2nd Iowa. The 2nd Iowa suffered 237 casualties, while the Sharpshooters had about 80. Corporal Doak and Company E emerged largely unscathed but were deeply affected by the surrounding death and destruction after "seeing the elephant."

Grant, who died exactly 140 years ago today (July 23rd, 1885), was well pleased with his western soldiers, writing in his official report on February 17th: "The victory achieved is not only great in the effect it will have in breaking down the rebellion, but has secured the greatest number of prisoners of war ever taken in any battle on this continent. Fort Donelson will hereafter be marked in capitals on the map of our united country, and the men who fought the battle will live in the memory of a grateful people." (Donelson Campaign Sources Supplementing Volume 7 of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion.)

I wish Grant was correct that the American people, even 163 years later, remembered and honored the Union soldiers who suffered and died at Fort Donelson. As noted above, I am sure few Americans know about this battle or how much Union soldiers suffered to unite our nation and achieve a "new birth of freedom."

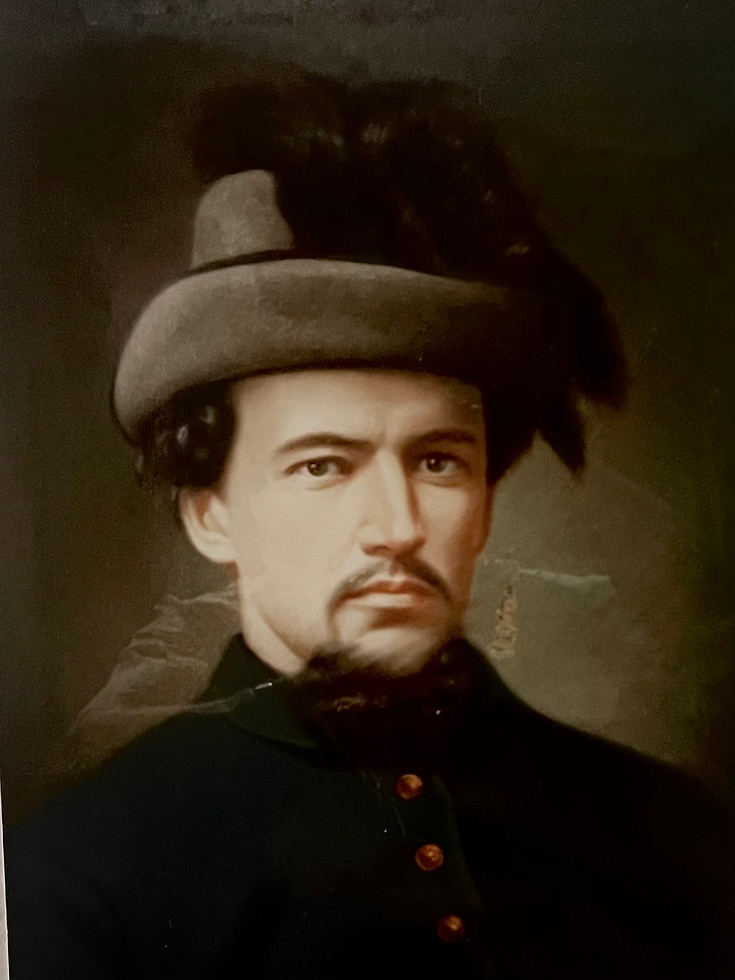

On February 22nd, 1862, the New York Times heaped more praise on "Birge's Western Sharpshooters": "Among the rest who disposed themselves along these ridges were Birge’s celebrated regiment of riflemen, and from that time forward, a secession head above the parapet was sure to go down with a hole bored through it about the size of one that might be made with a three-quarter auger. This regiment did most effectual service, each member with a gray felt cap whose top is rigged 'fore-and-aft' with squirrel tails dyed black. Their weapon is a heavy rifle with an effective range of about 1,000 yards. Lying flat behind a stump, one would watch with finger on trigger for rebel game with all the excitement of a hunter waylaying deer at a 'salt-lick.' Woe to the rebel caput that was lifted ever so quickly above the parapet for a glance at Yankee operations, fifty eyes instantly sighted it, and fifty fingers drew trigger on it, and thereafter it was seen no more. Writhing over on his back, the sharpshooter would reload and then twist back, in all the operation, not exposing so much as the tip of his elbow to the enemy."

I will give the last word to seventeen-year-old Western Sharpshooter Private Arminius Bill. The following is from his diary entry on February 17th. He describes what he saw as he and other Western Sharpshooters walked the battleground and began the work of burying the dead: "We saw dismounted cannon. Splintered and upset wagons. Dead men almost everywhere. The mauling of bodies is indescribable. Some have heads torn open and brains running out. Others have bowels torn open and entrails protruding. Some have arms or legs torn off. It is a ghastly sight, sickening to see and still more so to smell. We go back to camp satisfied that war is horrible." (Bill, Arminius. The Civil War Diary of Arminius Bill, Bill Memorial Library, Connecticut Digital Archive)

###

Owen C. Doak

July 23rd, 2025.

Comments